These Legs Were Made By Cycling

HERE ARE SIX AMAZING SETS OF CYCLISTS' LEGS, AND THE INSPIRED RIDING STORIES THAT HELPED SHAPE THEM.

Will you look at those legs? Sculpted quads. Gnarly scars. Razor-sharp tan lines. There’s a reason we gape when we see a nice set of gams on the group ride—they reflect thousands of hours in the saddle. Here are six amazing sets of legs, and the inspired riding that shaped them.

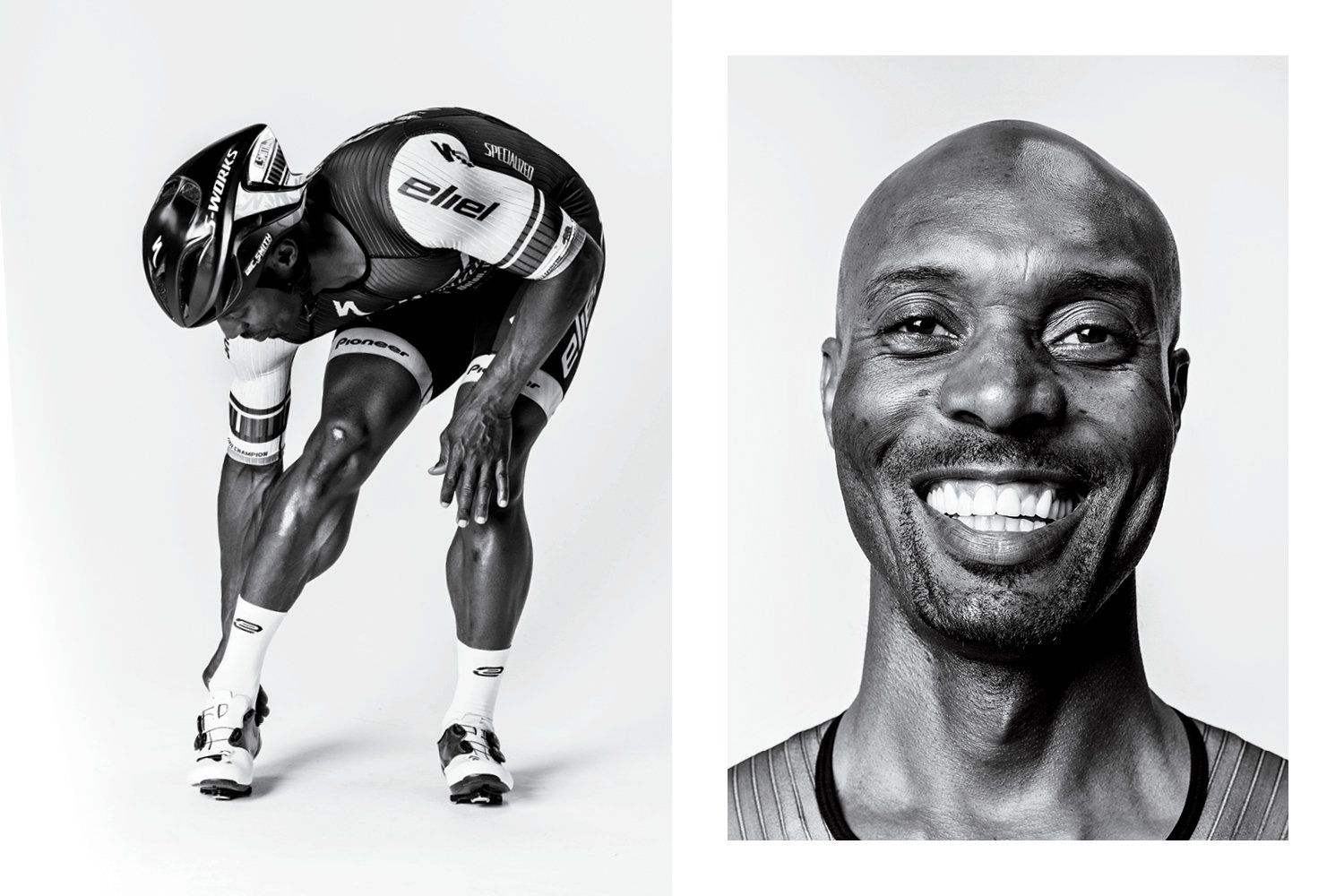

Charon Smith, 43

- Signal Hill, California

- California State Criterium Champion

“You gotta practice your winning pose because it’s gonna happen.”

It’s kind of funny how I got into cycling. I used to be a gym rat. There was a girl in the spin class that I wanted to meet. I said, I guess I got to take the class. I was like, man, this is a good workout. I went and bought a road bike on a whim. I bought too big of a road bike actually because I didn’t know anything about nothing. Then I found out about a race series by my house, at El Dorado Park in Long Beach.

At first I didn’t understand the dynamics. They used to ring this bell for prime laps. After a while, I asked someone, “Hey man, why when they ring that bell, everybody goes so much faster?” They said, “Oh, those are for points.” I started teaching myself how to place myself in a better position. I started winning races. Here I am now, 13 years later.

I do 10 to 15 hours a week of riding. I do a lot of hill work under stress. I’m ranging from 300 to 360 watts for a 5-minute effort in the big ring, and then I’ll recover. Then we’ll go to the next climb and do it again. When I do these workouts, they’re between 1 000 and 1 500 metres of climbing, just up and down the hills in Palos Verdes. This is done after work—I work 50, 60 hours a week.

My coaching company, Methods to Winning, focuses on strategy and mental game. We have a lot of talented guys here in SoCal. What was fascinating to us [Smith, and co-owners Rahsaan Bahati and Justin Williams] is that some of these guys who don’t get results on race day typically ride well on training rides. Myself, Rahsaan, and Justin, we’re very analytical when we race. Some people have these mental blockages when it’s time to pin a number on. I like to try to tap into some of the mental things that people deal with. Once you release the mind, the body will follow.

Even sometimes when I’m riding alone, I’ll practice a winning pose. One of my training buddies was like, “Man, Charon, what are you doing?” I said, “You gotta practice your winning pose because it’s gonna happen. You don’t believe it’s going to happen, so you never practice it.”

There’s also the art of losing: losing with dignity. Because we all could get beat. If you don’t learn how to lose, how are you going to learn how to win? If you fail at something and you don’t accept it, how are you going to dissect it? When somebody beats you, shake their hand, tell them, “good job.” You’re going to wake up tomorrow and maybe tomorrow’s going to be your day.

There’s a lot of little things that light a fire in me. One year I was told by a guy that I wouldn’t win a race the following year. I actually typed that on a piece of paper: “You will not win a race in 2013.” I laminated it, and I hung it up at work. Every day I saw that during the off season: You will not win a race next year. That became my motivation. I was like, I’m going to prove this guy wrong. I end up winning the first four races of the year.

I feel like there’s a lot of other Charons out there, but they just don’t know about the sport. I didn’t know nothing about this sport. I didn’t know it was so beautiful and it allows you to be so free and see so many things that you probably wouldn’t see. I’ve met some people that I never would’ve met. Here I am, Charon, the guy who grew up in South Central LA, and I’m hanging out with a judge, a doctor. Cycling has connected us.

Peter Stetina, 29

- Santa Rosa, California

- Professional road racer for Trek-Segafredo

“You have to keep letting your ass get kicked to come back stronger.”

Ah, the Frankenleg. It was stage one of Vuelta al Pais Vasco in April 2015. It was a 60-or-so rider sprint coming into downtown. I’m not a sprinting specialist so I was just finishing in the middle of the group, and we came around the final corner with about 1 kilometre to go. There were some metal parking bollards in the middle of the road that the organisers had neglected to notify us of, put a barrier in front of, nothing. Last minute they put a little orange cone on top of it. The first few guys saw it and swerved out of the way. I had no time to react: 65kph, blunt force impact, metal pole to my kneecap.

I shattered my kneecap into a bunch of pieces, cracked my tibia all the way down, tore my LCL [lateral collateral ligament], and broke five ribs. The fact that I even had a chance to walk was pretty good. I was non-weight bearing for three months, then rode my bike for three weeks and started the Tour of Utah. I was on a contract year, so I had to show teams that I could compete again some day. I was still walking with a cane, but I was racing Utah.

That first day in Utah, I was on cloud nine. I remember we did this big lap around a lake. It was pissing rain, everyone was bundled up in rain jackets, and I was so happy to be in the draft of a peloton getting sucked along again. There are parts about racing that suck and that I even hate today, but when it gets taken away from you, you realise how much you miss it. It was just about making the time cut, but I actually finished the week. I was pretty much pedalling one-legged.

I’m still not quite the athlete I was before and I don’t know if I ever will be. That’s something I still struggle with. There’s times, like the mountaintop finish in Tour of California last year, when I’ve perfectly peaked and psyched up for it, that I’m as good as I once was. But it takes extra motivation, luck, and timing. I was in the gym forever, trying to get 50/50 equal power in the legs. It’s 52/48 now which is actually in the realm of normal. But eventually I realised that I have to just focus on being strong and getting fast again because the body is really adaptive. Now I pedal differently, one leg uses bit more hamstring versus a bit more quad on the other leg, and my lower back takes up some of the slack. But the power is equivalent to before the crash. I still notice though after four or five mountain passes, in the hardest European races, that’s when my bad leg starts to give out. That’s frustrating because as an elite athlete you need that top 0.1 percent. But it’s not realistic to go to the gym and lift weights for four and a half hours and tire that muscle out so you can then work it in a fatigued state. I just have to keep racing. You have to keep letting your ass get kicked to come back stronger.

I have good and bad feelings about the scar. I’m proud of it. It has defined my work ethic and my career to a lot of people. It shows what kind of person and competitor you are to come back. At the same time, I’m also pissed. In my mind, what those organisers did is inexcusable and it was life threatening. There’s a lot of times when I think they shouldn’t be allowed to get away with this and this should have never been on my leg. There’s things, like the way it moves, that are gonna be a problem later in my life. I’m gonna need a knee replacement in my middle age years, that’s pretty certain. It definitely looks a little goofy, especially along the shin where the fascia was cut and you can see the muscle moving underneath—it looks alienesque. But I learned a lot about myself, and the scar represents a path of discovery.

If you’re having a crappy season you have to trust the process and trust that the body doesn’t always peak when you want it to. So many different things can make or break form—bad luck, crashing at an inopportune time. If you have good form, don’t waste it. If you’re flying in a race that’s technically a training race, and you’re good, you take that result. And don’t stress when things go wrong. It is just racing. It is just sport. At the end of the day no one gives a damn. No one really cares if you got sick. They forget in a few weeks. It’s really not that big of a deal.

Dana Feiss, 27

- Colorado Springs, Colorado

- Track sprinter on Team USA, four-time National Champion in sprint and keirin

“What a body can do is really amazing.”

As a track sprinter, all of our efforts are really short but very intense. You hit this line as fast as you can, and if you can’t see or if you throw up after, you did a good job. Everyone likes to say, “Oh the lazy sprinters, they go do four efforts and they take 20 minutes [of rest] in between.” It’s because we just turned ourselves inside out and now we need that full recovery so we can go and do it just as fast again.

Getting into that mental space repeatedly can be difficult. There are certain workouts that I just hate. The 500s [500-meter sprints] took me awhile, to get my brain around the pain: It’s gonna feel like you stuck a fork at the top of my hamstring and just ripped it down the length of my leg. But I kind of like it. I think there might actually be this psychotic element to sprinters. Being able to dig that deep, some people have it and some people don’t. I found out what my body is good at and I can push it in that way, to that extreme.

Because our races are so short and the margins are so small [often tenths of a second], a moment of hesitation could be make or break a race. We are gonna fight for it. That’s what our races ask of us. There’s a certain level of aggression and being able to tap into that at the right time: This is a two-up match sprint, it’s me or her. I’m gonna rip her heart out and eat it raw. It’s not personal, but I’m trying to kill you. The best sprinters, in my experience, will be totally crazy, absolute risk takers and then totally chill off the bike.

The thin margins can be a lot of pressure. When you go to the line you ask, “Have I done everything I need to do to this point?” If you can honestly say, “Yes, I’ve done everything possible. I’m here to do what I can on this day,” that’s what gets me over those nerves. Then you can relax and enjoy the bike race.

In a typical week, we do three double sessions—a gym session in the morning, then a track workout—and at least two road rides. I’m training 20 to 25 hours a week. I love the gym work too. If I had to hang up the bike tomorrow I’d go into power lifting or something. I think it’s great just to see how much you can get out of your body in a certain amount of time. What a body can do is really amazing.

One time in a coffee shop a guy said, “You have really nice legs.” I said, “Thanks, I grew them myself.” If you’re having fun and pushing yourself as hard as you can, your body is going to reflect that.

Patty Collins, 48

- Hackettstown, Virginia

- 2016 Paralympics triathlete, ITU World Champion Paratriathlete, and former US Army colonel

“Once I knew I could ride, I knew I was going to get everything back that I wanted.”

I went into the military in 1991 after college. My bike always came with me everywhere I went, and that was my way to explore. When I moved to the Washington, DC area I became a bike commuter, and dabbled in bike racing a little bit. I lost my leg from commuting to work one morning. I had come home from serving in the Army in Iraq without a scratch, in 2006. Six weeks later I got hit by a car riding a bicycle to work, which eventually turned into a below-the-knee amputation, in May 2007.

The first day I rode a bike after my amputation was July 4, 2007. It was my own Independence Day celebration. I went about a mile. There were a couple of spills with my prosthesis in my clipless pedals. But once I knew I could ride, I knew I was going to get everything back that I wanted.

I went back [to the bike after the crash] for a couple reasons. One, I loved it. And two, if I chose to not get back on my bicycle then I chose to say that cars win on the road. And I hate that there’s even a debate. Accidents happen, and the person that hit me wasn’t a terrible person, he was just for a split second not paying attention. So it was important for me to get back on my bike and say, “I am not going to let this fear consume me.”

When I felt comfortable enough on my bike with my prosthesis, I started piloting on a tandem for visually impaired athletes. That’s my favourite bike ride of the week. I’ve piloted a triple with two visually impaired ladies. That’s my proudest achievement on a bike—which has nothing to do with medals or records. We were riding back to the end of this 25-mile ride, and one of the ladies said, “Everyone who sees us is saying, ‘Why are those two ladies letting that crippled woman pilot that bike!’” It was pretty comical.

In the military, there is a phrase that we used called “shared hardship” or “shared challenge.” And a bicycle ride is the same way. If you and I are on a four-hour bicycle ride and it’s raining cats and dogs or it’s a lot of climbing or it’s hot or whatever, we’re sharing that hardship together, and we can’t help but bond through that experience.

Before my accident cycling was something I loved, but I took for granted. To lose it and have to relearn it, makes you really appreciate the gift. It’s very natural to say, “Oh, it’s raining out, I don’t want to do this workout,” but you get through it. You just have to take a moment and take a deep breath every time you ride your bike and say, “I am so lucky that I have this opportunity.”

Cait Dooley, 29

- San Carlos, California

- Product manager at GT Bicycles and cancer survivor

“Bike racing saved my life.”

I was diagnosed with thyroid cancer when I was 24. A couple months before, I’d quit my job [to race cyclocross full-time]. I’d thought I was overtrained, because I wasn’t feeling quite right. It took five months to figure out what was going on.

The recovery process was very, very difficult for me. I was in my 20s, and that’s when you should be doing all kinds of stuff, and feeling your best, especially in cycling. For a little while after surgery, I couldn’t even get out of bed by myself. My mom had to help me shower. I remember trying to wash my hair, and I couldn’t even move my neck to suds up. That was a pretty humbling moment.

I dealt with it by finding something positive to focus on and keep me motivated. I set goals, big and small. I had a little sheet of what I wanted to be doing in the next six months, year, a few years. I decided I wanted to work in the bike industry. And that I wanted to race the Trans BC Enduro.

I have the view that bike racing saved my life. If I hadn’t been paying so much attention like you do when you’re an athlete and you’re training, I don’t think the cancer would have been caught as early.

The “You got this” tattoo is bike-racing related. The women in the cyclocross field in New England, especially at the beginning of the season when everyone’s got the first-race jitters, we always said, “You got this.” I don’t know who said it first but it just kind of became our saying. I got it a year before my diagnosis, in 2011. When I got sick, my friend Chris made stickers and a ton of people put them on their bikes and on things everywhere. And for our end of the season team party, Chris also drew up this poster that had two unicorns on it that said, “You got this and we got you.” I cried then. So for me, that tattoo ultimately helped me realise how much of an amazing community I was in. People still have those stickers on their bikes and that was five years ago. We also worked with The Athletic and made socks. The proceeds went to First Ascents, a charity that takes youth and other people affected by cancer to the outdoors. The tattoo really has evolved in its meaning for me.

If I could give someone advice for recovering from an illness or injury, I think probably the most difficult thing for me, which took me entirely way too long to learn, be nice to yourself. You have to stop comparing yourself to when you were training 15 to 18 hours a week, versus just having had surgery for something pretty serious. That’s not a fair comparison. So you need to knock that off. Approach it like you’re learning how your body works all over again, and maybe err on the side of a little bit more recovery.

Carlos Da Silva, 69

- Ivyland, Pennsylvania

- Retired automobile shop owner

“You say to the body, ‘I work hard for you, now you’ve got to work hard for me.’”

I started riding sometime in ’88 or ’89. I did some racing, Cat 4 and Masters. I was in the automobile business for 40 years. I retired last October.

I am very strict with myself, training almost every day. I bike four times a week, between 300 and 360 miles a week. I did 410 miles in four days of riding in the spring, but that was overtraining.

On Tuesdays and Thursdays, I hit three groups. I join the “A” group in the morning at 6 a.m., which is mostly younger and very strong guys. Then between 8 a.m. and 9 a.m. I ride by myself, hit some hills on my own. Then I join a second group and I go an hour or two with them. Then a third one that goes pretty fast, about 55 or 60 miles. By the time I return home I get between 110 and 120 miles. I go to the gym in between and do the upper body and a lot of stretching. I also massage the legs with a stick. All of the little tricks help. You say to the body, “I work hard for you, now you’ve got to work hard for me.”

I used to play professional volleyball in South America. I played for 35 years. That made 75 percent of my legs, by jumping and plyometrics. When I was starting to bike I noticed the difference in volleyball, that I was running circles around everybody on the court. The bicycling helped in the stamina. I went back and forth. When I was on the bike, with the legs from jumping and doing plyometrics, that helped me with the sprinting on the hills.

When you’re 10, 15 years younger you depend on your power. “I can eat a little more junk, I can be a little bit heavier.” You blow up your legs. But as you get older you have to minimise the resistance, starting from the bike to your weight. I prepare my rice cakes, I juice in the morning. I eat very little red meat, mostly veggies. And I take a good recovery drink for right after riding which makes a big, big difference, which I never used to use. I’m the same weight now as I was when I was 20 years old.

I’ve learned timing and the study of the other guys: How they ride, where they are weak. When I was younger I didn’t pay much attention to that, I just depended on my legs and my strengths. For many years they used to call me “53/11.” I used to like not to spin. Then I started to use a heart rate monitor several years back. I tried to make my cadence higher and get my aerobic system up. Spinning for one hour in the gym with a cadence over 100 [rpm] at 150 to 250 watts nonstop. If you try to do it with 75 to 80 cadence, the legs are going to start to burn. I have a 25 [tooth cog] on the back no matter how big the hill is, but now I have a compact [crankset] on the front. It made me a little shy on some hills going 45 mph down, but we are not in France or Italy going down for miles, you don’t win anything going down the hill. It’s usually going up.

READ MORE ON: cycling legs fitness legs People QUADS