The Real Reason You Can’t Climb

Want 5% more performance in a month – and to be able to climb hills faster? The answer’s simpler than you might think.

A secret training method? Super-hard intervals? Specific hill repeats? Or some exotic magic bullet? It’s a lot simpler than all of these, and nothing needs to change in terms of training.

A group of professional cyclists was asked what the most important aspect of their race preparation was – and the answer was ‘body weight’. Granted, they ride for a living; but within each of us is a desire to perform as well as we can – and body weight is undervalued as a performance booster… or inhibitor.

Here’s an example. You’re on the start line of a race, you know you’re fitter and more powerful than the person next to you – but their svelte shape means you’re going to get hurt on the hills, or even get beaten in the race. That should be motivation enough for you to make some lifestyle changes, and lose a few excess kilograms.

Nothing drives the power-to-weight message home better than a sturdy climb. You’re either the one putting in the hurt, or the one taking the hurt. And while there are exceptions, the common denominator for cyclists pushing the pace on a big climb is that they’re light.

Power and weight are easily measured in cycling, which means the sport lends itself to better analysis.

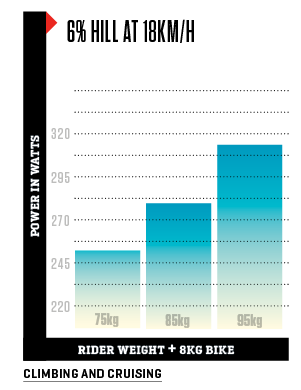

So, looking at the numbers, let’s see what’s happening in this scenario (see ‘Climbing and Cruising’, below: a moderate 6% gradient hill, three cyclists riding at the same speed, identical bikes, same threshold power of 300 watts – but with a 10kg difference in body weight between each.

A power output of 250 watts, for a rider in good condition, is a sub-threshold pace they could sustain for a couple of hours. At 313 watts, the extra weight on the heavier rider means he’s over threshold – and burning matches.

Now the hammer really goes down!

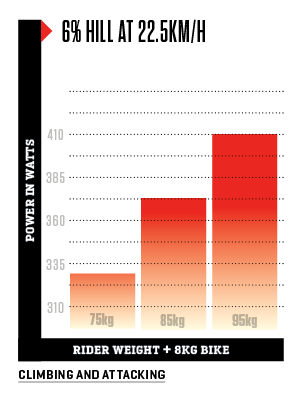

The light rider decides it’s time to attack on the 6% hill (see ‘Climbing and Attacking’, right) and accelerates to 22.5km/h, producing 330 watts of power. He’s now over threshold, though not so deep that he’ll be blown out the back within a couple of minutes. But what about the heavier riders?

Excessive anaerobic energy production

At 370 watts, the 85kg rider is digging deep. If the hill doesn’t crest within a few minutes, he’ll be blown. At 410 watts the situation is more critical, with under two minutes’ capacity before the heavier rider blows. And 6% isn’t even a steep hill; those power-demand variances become greater as the steepness increases.

The bottom line

The key performance factor for cycling and hill climbing is threshold power to weight. These graphs showing the relationship between power and weight give some perspective on why many riders struggle on hills, or are blown out the back.

That doesn’t mean you should start a cleansing or detox diet, a Banting diet, or any other fad. It’s just about controlling excess and eating clean, to shift fat and improve performance.

Spend just one week using a phone app or notebook to record EVERYTHING you eat, and make yourself aware of where any excess kilojoules are coming from.

Time to shift the weight balance!

READ MORE ON: cycling weight health strength training training weight loss