The Last Lion

After the 2024 Absa Cape Epic finished in Stellenbosch recently only two riders had finished every one of the 20 events.

Streaks are funny things, in sport. By the very fact of their unlikeliness, they capture the imagination of the public.

The two riders who have now finished every single Absa Cape Epic dice with disaster every year, just to make the finish of an event in which so many succumb to illness, injury or a disastrous crash. And you couldn’t find two more different people to have as the Last Lions of what is rightly billed the Untamed African Mountain Bike Race.

Former Springbok triathlete, duathlete and mountain biker Hannele Steyn is the Last Lioness – the only women to have ridden every one – and is a big part of Absa’s SheUntamed drive to get more women riding mountain bikes, and ultimately riding the Epic itself.

And then there’s John Gale, the quiet Cape Town accountant who enters every year, and sleeps in the tented village. We all did, in the early years; he’s kept doing so, because it’s as much part of the event as the riding.

And part of Gale’s success has been keeping it simple. As an accountant, his world revolves around minimising risk; and that’s the only reason, he believes, that he’s managed to notch up a full rack of finishes.

“It seems bizarre and unlikely. Although I rode Attakwas last week with my 2024 Epic partner, and he hasn’t even finished Attakwas twice. There’s an element of luck – or an absence of bad luck.

“I think it’s in your head, too. I’ve had to accept over the years that I find it difficult not to finish things, to walk away from things.

“But sometimes there’s no real reason. An Epic day is always bigger and harder than you would do ordinarily – you get to the point where it’s bigger than anything you’ve done. You get halfway, and your mind goes, ‘That’s enough’. But you carry on, and do it.

You get halfway, and your mind goes, ‘That’s enough’. But you carry on, and do it.

“These days, we go in prepared. And I’ve always made these races a family affair – included Beth and the kids. The early days were harder, having to get out of the house by 5am to be back to help with the kids. But they’re much older now, so I can manage that better.”

Howdy, pardner!

Gale has had a surprisingly small number of partners; all have been close friends, “because it’s an amazing thing; you get to spend eight days in a bubble with someone, outside the world, in a different, challenging environment. I’ve always ridden with people I know already, who are smart, with a sense of humour. I don’t meet people on the start line.”

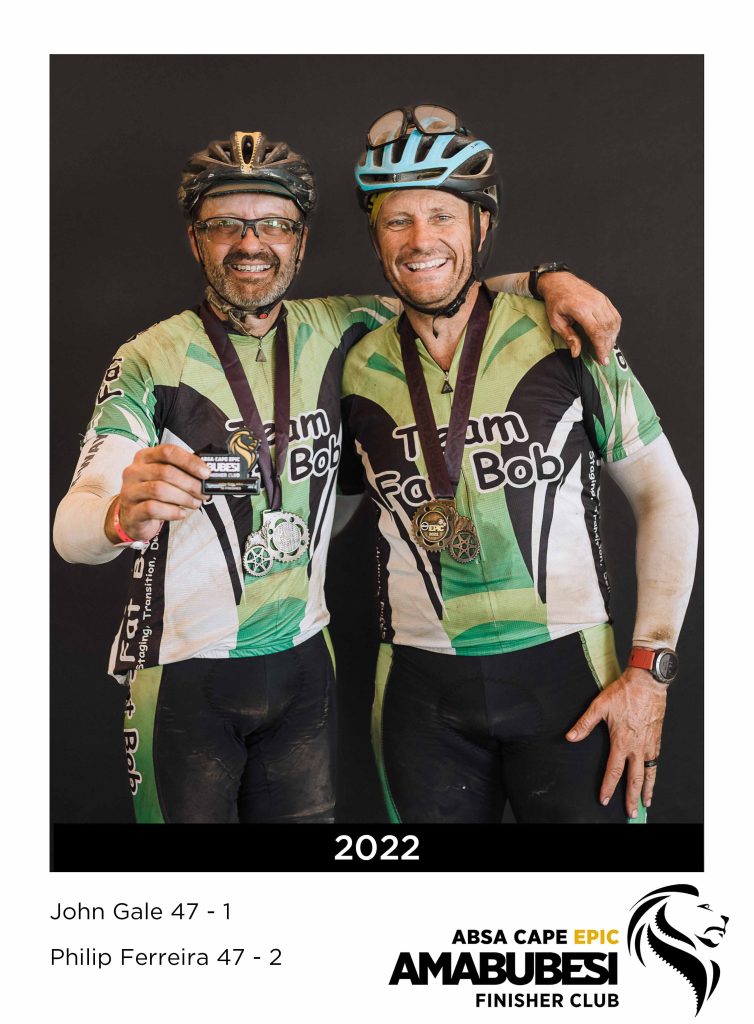

His 2024 teammate is a prime example. “Twelve years ago, Phil (Ferreira) said to me, ‘One day, I’ll ride the Epic with you.’ I said, ‘Ah, you big fat rugby player – not a chance.’ Now it’s happened.

“I’m not choosing anyone I don’t like, to start with. It’s an amazing privilege; you get to know people at a different level – there’s no escaping each other. Not just under stress, but all the time.

“And they’re so different. One’s a trial lawyer, and is always up for a fight. Another we call ‘40% George’ – he says things like, ‘John, I’m about to cramp; we need to back off.’ And does so like a startled hare. Rather flatteringly, he’s said he wouldn’t be bothered to ride with someone other than me.

“Riding the Epic brought all of us closer, as friends. Which is no small thing.”

Route matters

As one of the Last Lions, Gale is well placed to comment on the pros and cons of the clover-leaf configuration that in 2009 replaced the original journey from Knysna to Cape Town. “Logistically, it’s obviously much more efficient. The experience of travelling is very powerful, but obviously there are compromises you have to make when you have to cover distances.

“Technically, now, the variety of riding is much better with the clover leaf – increasingly so, as land access becomes more of a problem. More and more farmers are managing their security with cameras and electric gates – they used to like the ‘right kind of eyes’ travelling through their farms, but now it’s a pain when the field triggers sensors and cameras. The transition days are just going to get more difficult to build, I think.

“Do I miss the sense of travel? Yes. Do I enjoy singletrack? Yes I do. Did I enjoy the journey? Yes I did. Would I choose one over the other? Well… I enjoy both.

“The Epic is at the very top of the class in the events world. Clearly there’s still a huge demand for it, and there are powerful interests at city and provincial level which seek to promote these flagship events, which helps with the inconvenience and risk.

“We’ve kinda grown up with it. Back in 2003, my mate Jakes called and asked if I’d heard of this new race. I hadn’t; but we did it anyway. And it’s changed the face of mountain biking in South Africa – which in some ways is good, some less good.

“There’s a different kind of rider now. The ‘suck it and see’ crew is no longer around, the ones that ‘didn’t read all of the words, but I’ll give it a go!’ And increasingly, it’s harder to cross 40 or 50 landowners’ properties to put a stage together. That’s always been one of the amazing things about the route, getting all those landowners on board on the same day!

“Every year, I can’t wait to be on the start line. Even though it’s still a bit terrifying each time.”

The Memories

What was the hardest stage ever? And the hardest stage in history?

The first question is the easiest to answer, in Gale’s unique experience of the event: “They’re all hard. And you’re always going as hard as you can. So there is no hardest stage.

“If you’re stronger than your partner, it’s easier; if you’re weaker, it’s harder; and if you’re sick or injured… it’s just unbearable. I have lain under trees and hoped to feel better soon, often. And you do.

“One of the things we’ve had to learn to manage is the heat; there’s no doubt it’s got worse. It’s an external factor people don’t allow for. They can’t imagine what riding for that length of time could do to your body. For me, these days, it’s as much about just trying to keep your body cool enough to let you function later in the day.”

We look at each year in turn. For Gale, this means a mixture of lucidity and blur – as you would expect, with more than 150 stages and 15-odd thousand kilometres to go back over.

“I’ll never forget Stage One, in the very first year, climbing up that last tar pass to Saasveld. The longest race in South Africa then was about 80km; we had ridden 120-plus, and there was a guy with cramps, lying on the road, flapping like a salmon. ‘Ek’t jou mos gesê, dis nou genoeg training…’

“That day, we had no idea what to expect. At one stage there was a group of police directing us; and then, later on, there were some army guys with a Ratel and R4s, ‘forcing’ us up the mountain. Then you knew it was serious! I thought that set the tone.

“The very last day, someone had put out some Chuck Norris signs – to motivate us, I presumed. Things like ‘Saddle sores get Chuck Norris’. And then we got to the finish, and there was a sign saying, ‘Chuck Norris and friends are riding back to the start tomorrow, 05h00!’. In that first year… we had no clue.”

Gale nearly ruined his streak before it even started – by failing to enter the 2005 event in time. “I bumped into Mike Cheeseman, who had also ridden in year one, on the back of his many Berg River Canoe Marathon wins; and he told me he had an entry, but wasn’t riding. So we subbed, about three weeks before the event.

“I was suffering with terrible ITB at the time, training for Two Oceans; so my memories of that year are stretching, resting, stretching, resting… I did go to the race medic at one point, and he surmised, highly professionally, that it was an overuse injury, and that keeping on using the leg might allow it to get better… turned out, he was right!

“I’ve had a root canal during an Epic – a huge abscess – and I remember telling 40% George on the start line that I was feeling absolutely terrible. He nodded wisely; and sure enough, halfway through the stage I was feeling better, and we were back to normal.

“And then there was 2016, when I only just finished, with hepatitis. My partner Pierre had to take my bike on the last stage, and it was all I could do just to get to the finish line. There’ve been some close shaves.

“From about 2006, we got better at training and cleverer at finishing, I think. Our execution got smarter. And 2008 was great – George’s mother drove us to the start in Knysna, from Cape Town. And we all camped in the campsite before she dropped us off in the morning to ride back to Cape Town.”

The Failure

2023 was to be a different year for Gale. Until then, he’d been the only one of the Last Lions to finish every one of his 18 Epics with his team intact. It was the heat that changed the narrative.

“I was going to ride with Phil, but he tore a bicep – doing housework! – so I ended up riding with an old friend, Gavin Copeland. Stage One was terribly hot; but I think we failed to realise how hot. It’s like being a frog in boiling water; you just get used to being over your limits, and you keep going.

“Gavin was in a bad way – at one point I had to call to him not to ride into a pavement. And he was riding the singletrack into Hermanus terribly. Quite unlike him.

“I knew it was bad, but I thought they would just put him on a drip at the finish. But they took him to hospital, with renal issues – it was serious. We didn’t realise it, but a combination of anti-inflammatories and heat on the day meant seven guys ended up with a huge helping of that, and failed to finish.

“I hate that we didn’t make it; I see it as a failure, in a way. My job is not to finish the Epic, it’s to finish the Epic with my teammate – to do whatever we need to do to help each other make it to the finish each day. And I couldn’t do that.

“I hated it, but I don’t think either of us was aware of how hot we were getting. But your core is just getting hotter, and hotter, and hotter… He kept apologising for letting me down; but if anything, it was the other way round.”

That turned Gale into a solo rider for the remaining stages of the ’23 Epic. “That was a different experience. Part of the Epic is the working together, communication. So in a sense it was easier, because you only have to worry about how you are feeling. There are enough riders these days that you’re never really alone.

“In the early years, you felt quite exposed – like, if you crashed off the road or something, they might never find you. But it’s different now; it’s so big. Solo’s a different challenge. With a partner – which is the way it should be – you have to learn when you can go hard, and know how to manage both him and you, which is the challenge of the Epic. On your own… if you’ve had enough, you slow down; if you’re feeling good, you speed up.”

“I felt an element of failure. It’s not the riding – I don’t want to say that’s easy – but I didn’t complete the task as it was set out.”

The End

So how does it end for John Gale? What would put a stop to the streak? “I don’t really know – I guess, one year, I might just not feel like riding it. Something else might come up that’s interesting.

“But I don’t think that’ll happen soon.”

READ MORE ON: absa cape epic Cape Epic