The Science Behind Marcel Kittel’s Tour de France

Sprinters like Marcel Kittel can throw down huge watts for short periods, but how do they get through the rest of the Tour de France?

- A new case study featuring pro cyclist Marcel Kittel found he sustained a higher load and spent more time in the high-intensity zones in the mountainous stages of the Tour de France than other riders.

- This strategy, called a reverse pacing strategy, allows world-class sprinters like Kittel to finish the mountainous stages more efficiently.

What does it take to be a world-class sprinter in the Tour de France? To find out, researchers did a case study of former pro cyclist Marcel Kittel, a sprinter who won 19 stages in the three Grand Tours between 2011 and 2019.

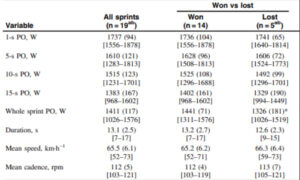

Published in the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, researchers looked at Kittel’s power output data from four different Tours, and analyzed the different stage types—flat, hilly, mountain, and time trial. They also looked at load, intensity, and performance characteristics.

The researchers found that Kittel—who, as a sprinter, excels in the flat and time-trial stages—sustained a higher load and spent more time in the high-intensity zones in the mountainous stages, which is called a reverse pacing strategy. That means the sprinter had adopted a different strategy compared to the rest of the peloton. Mountain passes at the beginning of the stage are executed above threshold so the sprinter doesn’t get isolated from the peloton, but this causes the rider to spend more time in a high-intensity zone compared to non-sprinters.

Kittel weighed between 90kg and his lightest race weight 88.5kg (in the 2016 Tour), which the researchers used to calculate his Tour de France Functional Threshold Power (FTP) in watts per kilogram for each of the races. His average power for each stage ranged between 256w (2.88w/kg) in 2017 and 264 (3.02w/kg) in 2016.

Kittel’s highest FTP was in the 2016 and 2017 Tours, in which Kittel pushed 431 watts (4.9w/kg) and 438w (4.9w/kg) respectively.

“One takeaway message from the study is that for sprinters like Marcel, finishing the Tour de France is extremely difficult, and around 10 percent harder compared to a general classification contender,” study coauthor Teun van Erp, Ph.D., a post-doctoral researcher in the Department of Surgical Sciences at Stellenbosch University in South Africa, told Bicycling. “The sprinters do not want to get isolated at the first climb, thus Marcel rides as fast as possible so he can do the race with a bigger group,” he told Bicycling.

This allows riders like Kittel to finish the mountainous stages more efficiently, van Erp said. But it also puts much more strain on the sprinter in subsequent sprints, since they need to maintain output to be as explosive as possible.

If it worked for Kittel and sprinters like him, does that mean you should give it a try on your own hilly rides?

“Absolutely not,” van Erp said. “I don’t think a non-racing cyclist should adopt this strategy in a normal training ride. Only sprinters should be using this strategy in the race.”

That’s because, as he noted, it takes much more power output and intensity with a reverse pacing strategy. If you’re conditioning yourself to use that tactic in the months leading up to a race, then it might be worth consideration along with other potential pacing strategies to see what tends to work best for you.

But in terms of everyday cycling, van Erp said this type of approach could cause you to lose power—and potentially bonk—much sooner than you would otherwise.

If you do want to get faster at sprinting and climbing, though, incorporating strength training and interval workouts on the bike into your routine can definitely do the trick.

READ MORE ON: marcel kittel power sprinting strength Tour de France