Canyon Launches K.I.S. Steering Stabiliser

It might look a little Heath-Robinson, but Canyon's new K.I.S setup might actually change the way we ride mountain bikes.

The Takeaway: Canyon and Liteville shake up trail bike handling with the K.I.S. steering stabiliser

- Three-part system—springs, straps, cam ring—hides inside the top tube.

- When turning the bar away from centre, adds resistance; when turning the bar back to centre, adds assistance.

- Adds just 70 to 100 grams to the bike.

- Claimed to improve bicycle handling and stability at all speeds and in all conditions.

Weight: Adds 70 to 100 grams to the bike’s overall weight.

If you thought mountain bike technology and geometry has, after about a decade of frenetic change, settled down, Canyon and Liteville and Canyon say, “Halte mein bier.” The two brands debut trail bikes today with a fascinating little doodad that hides inside the top tube and claims to improve a bike’s stability and handling at all speeds, and in all situations.

If you thought mountain bike technology and geometry has, after about a decade of frenetic change, settled down, Canyon and Liteville and Canyon say, “Halte mein bier.” The two brands debut trail bikes today with a fascinating little doodad that hides inside the top tube and claims to improve a bike’s stability and handling at all speeds, and in all situations.

What is K.I.S.?

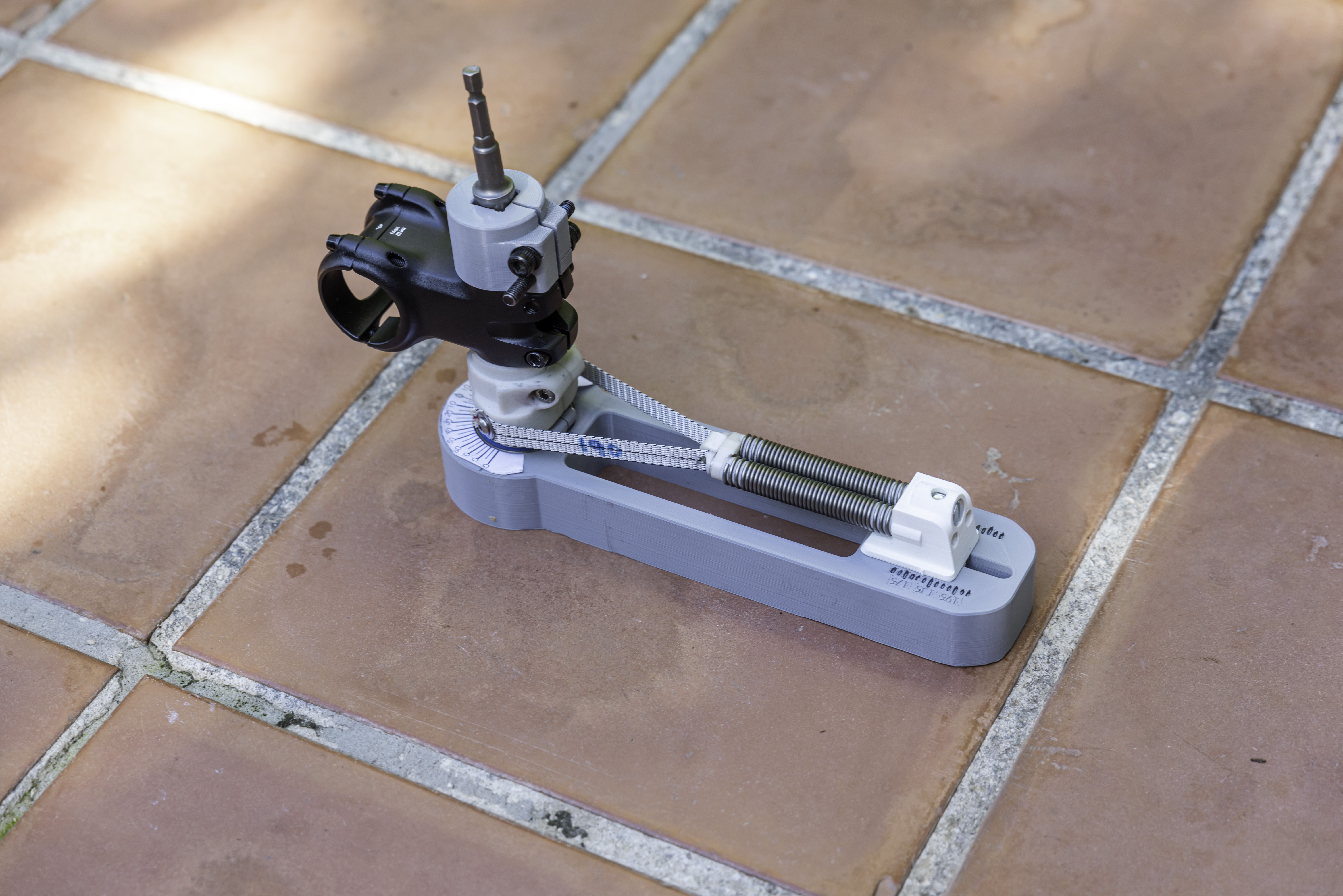

K.I.S. (Keep It Stable) is a widget, a contraption, and a gizmo that hides inside the top tube. It consists of springs and two Dyneema straps that anchor to a cam that slides over the fork steerer. The other end of the system attaches to the top tube at a single-bolt adjustment slider that lets the rider tune the spring tension. And that’s it. It’s quite simple, albeit quite goofy looking—It’s a good thing that it hides in the top tube.

When I first saw the system, I thought, “Is this a joke? I flew halfway across the world to ride this…doohickey?” And while K.I.S. will inspire its share of jokes and memes, after learning the story behind it and riding the system, I think there’s potential for this funky little doohickey to kick off a fresh look at geometry and bicycle handling that, potentially, benefits a wide range of bicycles.

K.I.S. debuts on bikes from Liteville and Canyon. Joe Klieber, founder of Syntace components and its sibling bike brand Liteville, invented K.I.S. and holds patents on its design. Canyon licenses the system from Syntace and has one year of exclusive use in the bicycle industry.

Canyon’s Spectral 29 CF 8 K.I.S. sells for around R8 000 more than the CF 8 without K.I.S. Riders will need to wait until Autumn 2023 to get their hands on the Spectral 29 CF 8 K.I.S.

What does K.I.S. Do?

K.I.S. increases the force needed to turn the bar away from center and decreases the force needed to return the bar to center. It’s like adding a spring to a screen door: You have to push harder to open the door, and, once open, the spring pulls it closed.

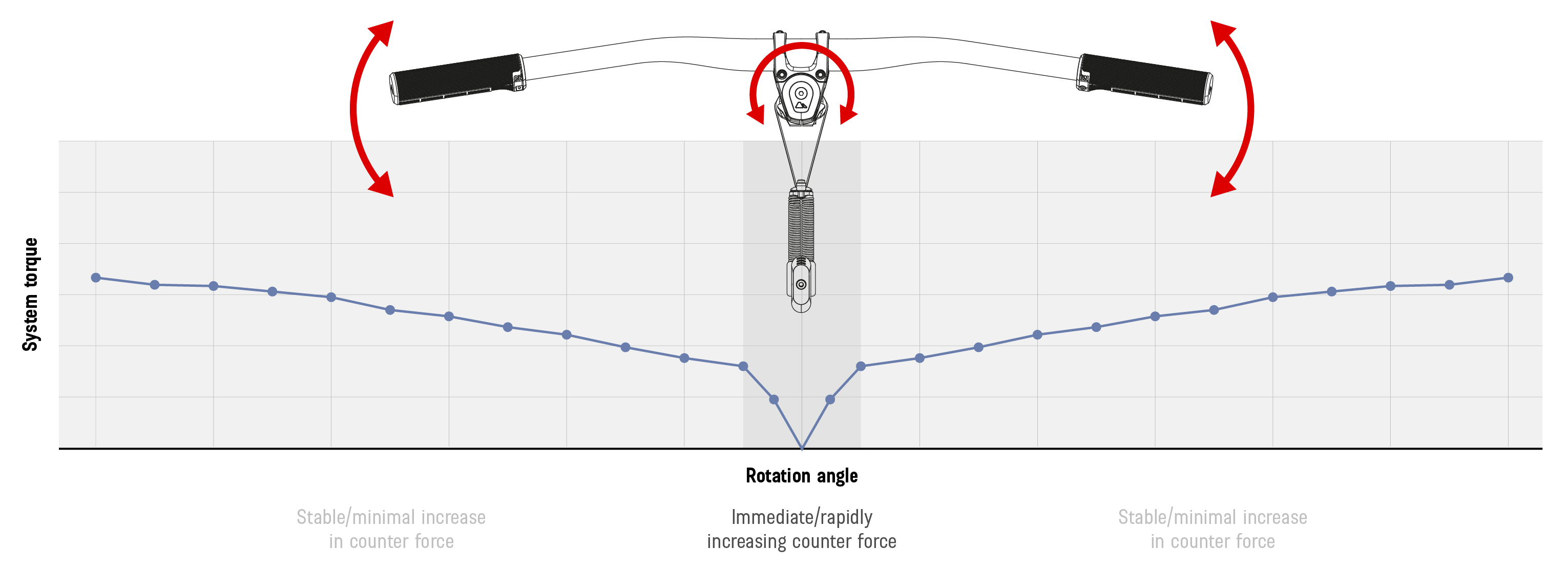

K.I.S.’s influence on steering can be non-linear and is tuned by tinkering with the length and rate of the springs, the length of the straps, as well as the shape of the cam ring that slides over the fork steerer.

K.I.S.’s influence on steering can be non-linear and is tuned by tinkering with the length and rate of the springs, the length of the straps, as well as the shape of the cam ring that slides over the fork steerer.

This ability to tune K.I.S. is evident in the two bikes that debut the system: Liteville’s 301 CE e-bike and Canyon’s Spectral 29 CF 8 K.I.S. Liteville’s tune is fairly linear, with an even amount of extra force added to the steering across the usable range. Meanwhile, Canyon tuned the system to offer a steep ramp-up in centring force initially, before flattening out as the bar rotates more.

Yeah, But What Does It *Do*?

The short version is K.I.S. adds (or increases) a centring force to a bicycle by increasing the torque required to turn the bar away from center and decreasing the torque required to return the bar to centre.

Rather than regurgitating the longer version, I’ll let the brands tell you what it does in their own words. Here’s what Syntace’s press kit has to say:

The main reason why the application of nonlinear symmetrical force improves vehicle stability and cornering handling, is rooted in the two-wheel vehicle’s native steering instability (as soon as they are built with a steering angle below 90°). This “wheel flop” lifts the steerer tube in straight position and lowers the front (stack height) when turning into a corner. Applying nonlinear force directly into the steering axis allows K.I.S. to counteract this native instability in the steering of two wheelers. By adding an accurate zero-degree position reference point and a relevant amount of centring force over the full range of steering improves control and precision (which has been known in most cars, trucks, tracked vehicles, airplanes, boats for decades.

And here’s what Canyon’s press kit says:

The addition of a central reference point and counter force when steering offers clear benefits to almost every aspect of riding. From increasing stability at any speed and more predictable handling to filtering out front wheel deflections and reducing rider fatigue, K.I.S even helps to control drifts and minimise understeer. When the trail heads back uphill the system keeps on giving, making climbing more efficient by actively combating wheel flop, reducing the power surges required from the rider to maintain balance.

Fun With Flop

Notice that both brands make reference to “flop”. Flop is a word that gets used in a couple of different ways when discussing bicycle handling.

One is the sensation of the front wheel flopping. For example: When trying to climb a steep hill the rider often feels the front wheel wandering and trying to twist 90 degrees. But you also can feel the bars trying to twist out of your hands when riding through a rocky section at speed. We spend a lot of time on the bike fighting (by pulling and pushing with our hands) this flopping sensation while trying to keep the wheel pointed in the direction we want it to go, instead of the direction it is trying to go.

The other flop is a dimension related to a bicycle’s steering geometry. But the importance of it, and even how it is measured, are not a settled topic. I’ve seen it described as the distance from the ground to the surface of the tire taken from an imaginary line drawn through the steering axis, and I’ve also seen it as the result of the equation—ƒlop = t sin θ cos θ (with t=trail and θ=head tube angle).

How much the sensation of flopping has to do with (or even if it has to do with) a dimension calculated as flop, is, as far as I can tell, not fully understood. Neither is how flop (however calculated) affects handling. It has something to do with steering and stability (or a rider’s perception of stability) and is very related to head angle, fork offset (rake), and trail. This means it is also related to the tire’s contact patch, available traction, rider weight distribution, bike attitude, and so on.

Whatever flop (the dimension) is and does, however, I’ve never seen or heard about it being used as something bike brands target or tune. It’s a result, not a goal, of the other, more common, tools used to create a bicycle’s individual handling properties.

Isn’t this a steering damper? Haven’t these been tried before?

Whether or not this is a steering “damper” may be a matter of semantics and is likely to be debated. For their part, Canyon and Liteville insist it is not a damper—Syntace’s Klieber opined that steering dampers are “shit” in his presentation to the press—and instead refer to it as a “stabiliser.”

Various attempts at steering dampers for bicycles have been tried. I’ve been around long enough that I recall testing the Hopey hydraulic steering damper (which I thought was pretty neat), while Cane Creek’s ViscoSet is a more recent example. And despite the insistence that K.I.S. is not a damper, there is some overlap in the purported benefits of K.I.S. and steering dampers. Namely stability and greater control.

Here’s what Canyon says in their K.I.S. press kit:

Previous steering stabilisers commonly found on motorcycles add friction through hydraulic damping that reduces ‘unintended input’ from the rider, or bike, and helps prevent speed wobble and ‘tank slappers’. The downside of those earlier steering damper systems is that they add a lot of friction to the steering.

Spring stabilisers are also found on some urban and kids’ bikes. These commonly use a single spring and make it progressively harder to turn the bars through their range of motion. K.I.S. is different to both of these types of systems. K.I.S. is designed to stabilise the steering, not to restrict it. Cleverly harnessing spring tension to create a unique self-centering force, without adding friction, the benefits of K.I.S. are not only felt when you are steering in a straight line like other systems. K.I.S. works throughout the steering range to help you stay on track in any situation.

I’ve ridden bicycles with steering dampers, though not recently, and K.I.S. felt different. While I liked the sensation of extra stability, the other steering dampers also made the bike’s turn-in sludgy and numb, and the steering felt notchy. K.I.S. didn’t have those drawbacks and, counterintuitively, the bike felt more agile because it was more stable.

K.I.S. Ride Impressions

I had my first opportunity to ride K.I.S. on a Liteville 301CE e-bike and a Canyon Spectral 29 CF 8in the Maritime Alps of France. However, these were trails I’d never ridden before, and frankly, the group spent more time driving around, doing photography, and waiting around to do photography than we did actual riding. To say my impressions aren’t fully fleshed out is not an understatement.

But I did try the K.I.S. in several different settings, as well as taking advantage of a feature of the specially prepared bikes by switching the system “on” and “off” between runs, and sometimes mid-trail. Production bikes will not have the ability to shut the K.I.S. off without fully removing the system from the bike. This can be done without harming the bike and (barring a few extra holes) turns it into a stock non-K.I.S.ed bike.

Firstly, and for better or worse, I found the effect of the system more subtle than I anticipated. The bars are not hard to turn, and they don’t yank back. I didn’t feel like my arms were working extra hard to steer and control the bike. After my first few trail sections, I found myself thinking, “Is it actually doing anything?” And based on conversations I heard the rest of the journalists having, I wasn’t alone. So, if you’re hoping, or worried, that a rider can hop on a K.I.S.-equipped bike and suddenly KOM all the segments, I’m going to take a flyer and say it ain’t gonna happen.

But after two days—I got a second bonus day on the bike that most journalists didn’t—on a K.I.S. bike (I spent most of my time on the Canyon Spectral) I’m ready to say it does do something, and it is positive.

If I were to simplify it using common benchmarks, I’d say the K.I.S. makes a bike feel like the head angle is a bit steeper than advertised on the climbs, and a bit slacker than advertised on descents. K.I.S. makes the bike feel slightly more stable on all sections of the trail without the common drawbacks associated with adding stability. I also felt like the bike stood up out of a turn more quickly and easily (especially when I had it in the highest setting). I felt like it was easier to say on the line I wanted and was less likely to be pushed or bounced off-line, and I didn’t jam the sides of ruts as often.

If I were to simplify it using common benchmarks, I’d say the K.I.S. makes a bike feel like the head angle is a bit steeper than advertised on the climbs, and a bit slacker than advertised on descents. K.I.S. makes the bike feel slightly more stable on all sections of the trail without the common drawbacks associated with adding stability. I also felt like the bike stood up out of a turn more quickly and easily (especially when I had it in the highest setting). I felt like it was easier to say on the line I wanted and was less likely to be pushed or bounced off-line, and I didn’t jam the sides of ruts as often.

Drawbacks, none that I noticed after adapting to the system. Although the first time I put it in the highest setting, I did feel like the bike’s increased snap out of the corners caught me off guard. Instead of coming out, for example, of a left corner and going straight, I’d transition out of the left and flip right, over centre, and start to initiate a right turn. This went away once I got used to the lighter touch needed to bring the bike out of a corner.

A lot of the changes to mountain bikes in the last decade-ish improved stability: Slacker head angles, lower bottom brackets, longer front centres, longer wheelbases, bigger wheels, dropper posts, short stems, and wide bars. Even if it primary reason wasn’t for stability, one of the side effects of these changes was increased stability.

And taken together, mountain bikes today are far more stable at speed, and in steep and technical terrain. But there’s almost always a compromise: When you make a bike more stable in one condition, you’re likely making it less stable in another. Rake out the head angle and a bike gets more stable at high speeds, but less stable at low speeds. It’s hard to make a bike dead-nuts stable on a fast and steep downhill chute without making it clumsier and vaguer when climbing a steep pitch.

Recently I’ve noticed that fewer new bike launches are filled with the talk of “lower/longer/slacker” than they were with the previous generation. It seems like, for now, we’ve reached how far geometry can be pushed (though Geometron’s Chris Porter likely disagrees) for improved downhill performance without encountering negative effects—sloppy and lifeless handling—on slower and flatter sections of trail.

That’s why I’m intrigued by K.I.S.: It seems to make a bike’s handling more accurate on climbs and also more stable on descents without taking on any additional compromises. Well, other than 100 or so grams of additional bike weight.

Where Does K.I.S. Go From Here?

For this initial launch, K.I.S. is being added to existing mountain bikes with no changes to their geometry. But I think it begs the question that, if it works as advertised, does it then mean a rethink of our current thinking about geometry is in order? I’d be interested to experiment with both K.I.S. tuning and bike geometry to see what shakes out.

It probably goes without saying, but both Canyon and Liteville expect to add the system to more bikes in the future. And, if you buy its benefits, you can see the potential for riders of bike categories outside of trail bikes. Triathletes riding on the extensions in tricky crosswinds, for example. Syntace/Liteville is also thinking beyond bicycles. The companies were recently purchased by Pierer Mobility (parent of KTM, Husqvarna, and GasGas motorcycles) and there are strong hints that K.I.S. might turn up in that space as well. Pierer also owns Felt and R Raymon marques, and I expect to see it turn up in those brands after Canyon’s one-year exclusive on K.I.S. is up.

And if K.I.S. is embraced by the riding public, I’d expect a fair amount of experimentation—and perhaps the development of similar systems—by other brands’ employees as they attempt to experience the system for themselves.

As for me, I’ve confirmed that a K.I.S.-equipped Canyon Spectral is shipping my way. I look forward to riding on my local trails as I attempt to get a better handle on the system’s effects and benefits, and giving it to my circle of testers for their feedback.

READ MORE ON: new releases new tech products reviews top tech